Programming Like a Pianist

February 19th, 2021

Tyler Cowen asks: “What is it you do to train that is comparable to a pianist practicing scales? If you don’t know the answer to that one, maybe you are doing something wrong or not doing enough.” I’m a software engineer, so let’s answer that question for software engineers!

First, we need to figure out why pianists practice scales in the first place.

What’s the point of scales?

I spent almost a full decade of my childhood playing piano. I wasn’t particularly good, but I managed to reach the highest level (10) in California’s Certificate of Merit program before quitting at 14. I think my modest success is entirely due to the sheer amount of time and practice I put into piano. Every afternoon after school (and on most weekends too), I practiced for a full hour. Summed up over 9 years, that’s more than 3000 hours of dedicated practice time! I began each practice by working through a set of scales and études. Why? Scales have two main purposes:

- Scales literally warm up your hands. If it’s a cold day, you need to get blood flowing in your fingers to have any chance of playing a serious piece.

- More importantly, scales help pianists develop muscle memory and finger dexterity. This fluency is a prerequisite for anybody playing music. If a pianist hasn’t mastered the basics, they’ll be too focused on the physical demands of a piece to worry about musicality.

Scales build the foundation on which musicians can produce beauty. They help pianists abstract away the machine and focus on the music, and are one of the main ways a pianist builds unconscious competence. Pianists aren’t the only ones who need unconscious competence—so do programmers, and so do athletes.

Scales for athletes

Before diving into software engineering, let’s answer an easier question: what’s the equivalent of practicing scales for athletes? Like pianists, athletes regularly practice their craft. Athletes also warm up before both practice and performance. Scale-equivalents appear in athlete’s preparations across many sports:

- Sprinters incorporate form drills into their warmups. These drills emphasize or exaggerate one part of proper form. They help athletes build unconscious competence so that come race-time, their form comes naturally.

- Basketball players religiously practice shooting from all over the court. The best shooters practice the most. During games, players are focused on a million different things—and none of those are shooting the basketball. All that practice built up muscle memory, to the point where Steph Curry’s form looks exactly the same shot after shot.

- Batting practice for baseball players looks just like shooting for basketball players. Studies have found that baseball players only have 150 milliseconds to decide whether to swing as well as where, when, and how hard to swing. Any athlete also deciding how to swing is toast.

Scales help pianists develop unconscious competence of the act of physically playing the piano. This frees up valuable mental load for pianists to focus on the musicality of the piece instead of the mechanical actions required to play it. We see the same pattern across sports, where drills and focused practice help athletes perform at their peaks during competition. What’s the equivalent for software engineers?

Scales for software engineers

To answer that question, let’s take one more detour: what are sources of cognitive load for software engineers? Here’s an (incomplete) list of things an engineer might need to have in mind when tracking down a tricky bug:

- What’s the problem I’m trying to solve?

- How do I reproduce the bug?

- Where in the codebase am I now? What’s the stack of functions I’m working with?

- What have I already tried, and what do I know won’t work?

- What’s my current set of hypotheses, and how would I confirm or invalidate each one?

- How do I mechanically transform my hypotheses into code?

All of these things require space in our engineer’s working memory. In fact, our engineer’s ability to fix this bug is limited by their ability to hold context in their head. What can engineers practice to minimize cognitive load and solve more problems? One approach that closely mirrors practicing scales is developing tooling proficiency.

An engineer that’s proficient with their tooling is naturally going to be more effective than one who isn’t. If you’re an engineer, think back to the last time you learned a new tech stack. How productive were you compared to your “home” stack? You need to keep track of so much more than just language differences—you need to think about changes in the IDE, how your environment updates with your code, even where you look for help online. All of this combines to bring even the 10x-iest of developers to their knees when trying a new stack for the first time.

And tooling proficiency is much more than just knowing your tech stack. Here are some other important aspects:

- Typing ability. Can you touch type? Can you type fast? If not, you’re using valuable mental cycles on physically expressing your ideas.

- Keyboard shortcuts. Searching through context menus is a great way to forget what it is you wanted to do in the first place.

- Window management. Navigating between editors and browser windows can be a huge source of frustration. I use Rectangle to help organize my windows and Tab Ahead to make browser tab management a little bit easier.

- Notifications. This is pretty easy: mute your notifications when you’re trying to get work done.

- Text editing. Vim and Emacs are the obvious examples here, though I personally don’t use either. Beyond that, I’ve been experimenting with text expansion for common tasks.

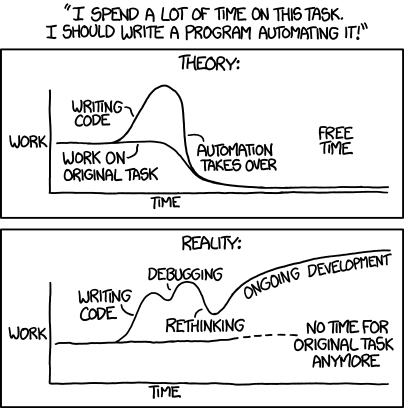

A failure mode to avoid

Don’t spend too much time on developing tooling proficiency! It’s easy to feel productive while hacking on your .vimrc, but it’s important to remember that tools are only meant to improve your productivity. I personally don’t use vim or emacs—I have a tendency to tweak to a fault, and either of those would encourage that proclivity.

A second downside to over-tweaking is that you’ll be ineffective on any machine other than your own. Prefer to build proficiency with default applications and shortcuts, and only introduce custom tools and shortcuts intentionally.

Conclusion

Scales help pianists develop dexterity and proficiency over the physical component of playing the piano. This helps them focus on the important part of piano-playing: musicality. Similarly, drills and skills practice help athletes free up cognitive capacity to pay attention to the competition itself. To achieve the same effect, software engineers should become proficient with their tech stack and tooling. Engineers that do this can hold more context in their mind, which makes them better engineers.