Body Composition For Sprinters

December 5th, 2020

What’s the lowest body fat percentage I can sustain without risking injury or losing strength? How much should I focus on hypertrophy? What’s my ideal competition body weight? How should I manage body composition throughout my season?

As a self-coached sprinter, I knew that body composition mattered. But I was overwhelmed by the complexity of the subject and the sheer quantity of often-contradictory information. After many hours of research and years of experience, I’m ready to cut through the noise and share my learnings. In this essay, you’ll learn:

- What body composition is, why it matters, and how to measure it

- Specific, research-backed targets for each body composition metric

- Why feedback loops are the best way to improve body composition, and how to establish them

My background

I’ve been sprinting competitively since I was 11. I was a captain of my university track team and held the 60m school record. Since graduating, I’ve continued to train as a self-coached athlete. I’ve learned so much operating without a coach. Now, four years into my career as a solo athlete, I’m faster than I’ve ever been.

Let’s dive in!

What is body composition?

Body composition measures your physical attributes and how well-suited they are for sprinting. Unfortunately, no single metric can fully describe body composition. It’s a latent construct — a theoretical measurement that can’t be directly observed. Instead, we must use proxy measures that each capture part of body composition. Combined, these measures can give us a sense of overall body composition. Some measures that are important for body composition are height-normalized weight, body fat percentage, and power output.

Weight

Sprinting is ultimately about propelling your body horizontally as fast as possible. Holding force production constant, lowering your weight means you can move faster! Of course, it’s rarely that simple. Losing weight often reduces your force production. And if you’re building muscle, gaining weight can still make you faster.

Weight is tricky to measure on its own because athletes’ heights are different. Instead of measuring weight directly, we can use a height-normalized metric. BMI is the most well-known measure for height-normalized weight. Other measures include the ponderal index (PI) and reciprocal ponderal index (RPI). These metrics let us establish benchmarks for weight that apply regardless of height.

Body fat percentage

In competition, fat is just dead weight — literally. If you are carrying too much body fat, you’re wearing a weight vest every time you compete. Dropping excess fat without losing muscle is a surefire way to get faster.

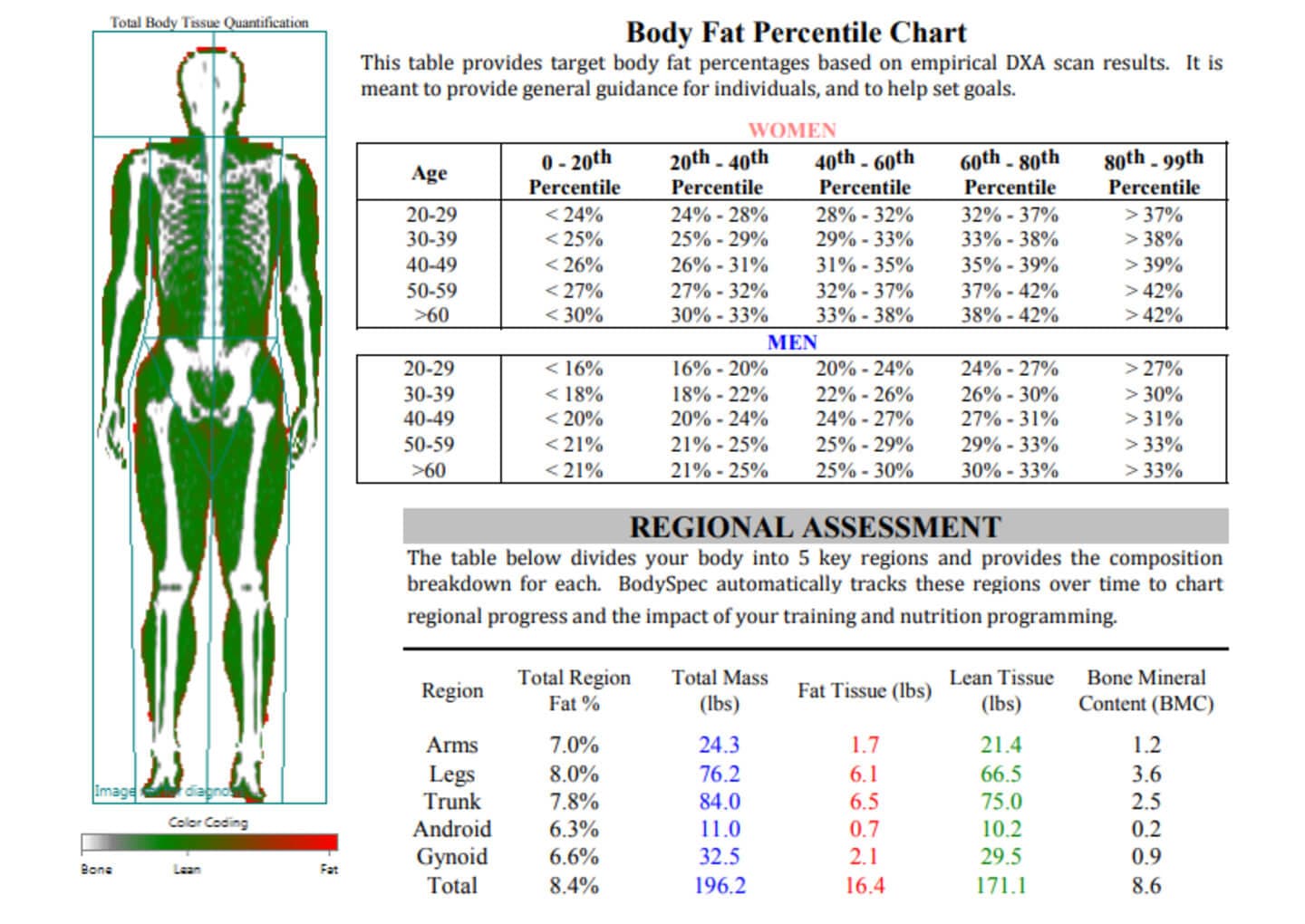

Be wary of calipers and consumer digital scales which are neither accurate nor precise. DEXA scans are the gold standard — opt for them if you can.

Power

Power measures your ability to exert force explosively. This is extremely relevant: when sprinting, your foot touches the ground for about 0.1 seconds. Your speed comes from whatever force you can exert onto the ground in that 0.1 seconds. Improving power means you can exert more force, which moves you along the track faster.

Unlike weight and body fat, power isn’t obviously related to body composition. However, power primarily derives from physical attributes: muscle mass, muscle type distribution (Type I vs IIA vs IIX), CNS adaptation, and more. None of these attributes perfectly correlate with power. Therefore, we should try to directly measure power.

Because power is muscle-specific, we need to measure power across multiple dimensions. To build a holistic picture of your sprint power, test your hex bar deadlift 1RM, standing vertical jump, and standing broad jump. These directly test your hip and leg musculature that impact sprint performance most. Unlike power cleans, these tests don’t require specific training, and unlike sprinting or standing triple jump, they are specific to power.

Body composition metrics for speed

You may have noticed a common refrain: speed comes from improving horizontal force production relative to bodyweight. This is your power:weight ratio (PWR) — and it’s the best predictor of your sprint potential. Keep in mind that sprint potential is not the same thing as sprint performance. Sprinting isn’t just a physics problem. Factors beyond PWR that make up sprint performance include reaction time, posture and form, and block starts. For body composition, however, PWR is the most important.

Ryan Flaherty, the “savant of speed” now working with Nike, has popularized a great proxy for your PWR. He calculates an athlete’s “force number” by dividing their max high-handle hex bar deadlift by their body weight. For example, in September, I maxed out my hex bar deadlift at 600lbs while weighing 193.8lbs - so my force number is 600/193.8 = 3.10.

Although Flaherty makes some outlandish claims (like that force number and 40 yard times are 99% correlated), your force number is still good to measure. Flaherty suggests that to run a 4.4 40-yard dash, you should target a force number around 3.2. He’s also mentioned that Usain Bolt has the highest force number he’s ever recorded — at 3.9.

Force number and PWR are important, but remember: as a sprinter, your most important metrics are your race times. Don’t fall victim to Goodhart’s law. If you’re spending all your time pumping your hex bar numbers, don’t expect to get faster!

Optimizing body fat percentage and bodyweight

Although improving PWR should be your primary focus, it’s also important to keep an eye on your body fat percentage and bodyweight. Surprisingly, few studies have measured elite sprinters’ body fat and bodyweight. What does exist suggest that elite male 100m sprinters generally have body fat percentages between 7-10% and BMIs between 23-26. There’s also weak evidence that

[n]ot only sprinters are heavier than their long and middle distances counterparts but within their distance, the fastest athletes are also heavier… Olympic champions in sprinting events are heavier than the finalists and the other participants.

Given the data, you should focus on meeting those BMI and body fat benchmarks. Prioritize whichever will improve your PWR first. Skinny high school athletes without a history of weightlifting should spend time in the weight room first and reduce body fat later. Already-strong athletes, on the other hand, may need to focus on cutting body fat. If you’re already within both ranges, work on your PWR — if you believe the research, this may involve gaining weight (while staying under a BMI of 26).

These numbers only apply to adult men. Women should not cut to 8% body fat!

Don’t cut during the season

Minimizing body fat comes at a cost. It requires prolonged calorie deficits, which slows recovery and increases injury risk. During the competitive season, this is too much for your body to bear. You’re already under tremendous physical stress — adding a calorie deficit is a recipe for disaster. Instead, you should only make significant body fat changes during the offseason.

Goalsetting

Here are my body composition goals for the upcoming season:

- Maintain my body fat percentage at around 8%. I’ll track this with DEXA scans every three or four months.

- Increase my in-season body weight from 193 to 198lbs. This will put me at a BMI of 25.4, towards the upper end of my recommended range. As long as I’m adding mostly muscle, my PWR should improve.

- Improve my force number from 3.1 to 3.5. At 198lbs this means a hex bar deadlift of 693lbs. The extra power should improve my acceleration and top speed in competition.

Tracking body composition

It’s all too easy to lose the thread with body composition. Left to my own devices, I tend to quickly lose weight (aka muscle mass) and get slower as a result. By regularly measuring weight, body fat, and power output, you can establish feedback loops to keep you on track. Feedback is crucial. For example, this past Thanksgiving, I had a little too much ham — by the next morning I had gained three pounds! I spent the next week eating carefully so my weight would normalize. If I hadn’t been weighing myself daily, my weight would have likely stayed elevated and I wouldn’t meet my goals. Here are some tips for body composition tracking:

- Weigh yourself daily. I use this digital scale which automatically syncs my weight with Apple Health. Make sure your measurements are consistent. For example, I weigh myself:

- Immediately after waking up and using the bathroom

- Without clothes on

- Before eating or drinking anything

- Test your hex bar deadlift. I test at the beginning and end of my competitive season and every eight weeks in the offseason. Combined with your weight, this helps you keep track of your force number and PWR.

Here’s my (high handle hex bar) deadlift max from last week - 600 lbs pic.twitter.com/fHL5EIak6k

— Jeff (@iambald)

- Measure your body fat with a DEXA scan 1-4x a year. Although DEXA scans are less convenient than at-home methods, they’re the gold standard for body fat measurements. DEXA scans are great checkpoints for overall body composition. At least in the Bay Area, they’re widely available. I’ve had good experiences with BodySpec — they’re about $40 per scan and only take five minutes!

Conclusion

Body composition is one of the most crucial aspects of sprint performance. Consistently measuring and improving your body composition will make you faster. Once more, here are the key points, distilled from hundreds of hours of research, that have helped me improve as a self-coached sprinter:

- Prioritize power:weight ratio (PWR). The force number is an excellent proxy for PWR. Measure it by dividing your hex bar deadlift 1RM by your body weight. Target a force number of 3.2 or more.

- Elite sprinters have body fat percentages around 7-10% and BMIs between 23-26. These are approximate targets which you should adjust for yourself. Don’t focus on these during the season, since the added physical stress can slow recovery and cause injury.

- Feedback loops are critical to improving body composition. Regularly measuring bodyweight, PWR, and body fat help you create behavioral feedback loops. These feedback loops will keep you on track with your goals.

- Keep an eye on your goals. You’re not a bodybuilder: don’t let body composition tweaks detract from your season.

With these tools, you can improve your body composition year over year. You’ll enter every season healthier, stronger, and (most importantly) faster than the one before!

References

- Sedeaud, A., Marc, A., Marck, A., Dor, F., Schipman, J., Dorsey, M., Haida, A., Berthelot, G., & Toussaint, J. F. (2014). BMI, a performance parameter for speed improvement. PloS one 9 (2), e90183.

- Barbieri, Davide & Zaccagni, Luciana & Babić, Vesna & Rakovac, Marija & Mišigoj-Duraković, Marjeta & Gualdi, Emanuela. (2017). Body composition and size in sprint athletes. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. 57. 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.06925-0.

- Watts, Adam & Coleman, Iain & Nevill, Alan. (2011). The changing shape characteristics associated with success in world-class sprinters. Journal of sports sciences. 30. 1085-95. 10.1080/02640414.2011.588957.

- Khosla T. (1978). Standards on age, height and weight in Olympic running events for men. British journal of sports medicine, 12(2), 97-101.

- The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts: Ryan Flaherty (#238)